Existing Policies

In their 1976 paper “VMIN — An Optimal Variable-Space Page Replacement Algorithm”, Prieve and Fabry outline a policy to minimize the fault rate of a program at any given amount of average memory usage (averaged over memory accesses, not real time). VMIN defines the cost of running a program as C = nFR + nMU, where n is the number of memory accesses, F is the page fault rate (faults per access), R is the cost per fault, M is the average number of pages in memory at a memory access, and U is the cost of keeping a page in memory for the time between two memory accesses. VMIN minimizes the total cost of running the program by minimizing the contribution of each item: Between accesses to the same page, t memory accesses apart, VMIN keeps the page in memory if the cost to do so (Ut) is less than the cost of missing that page on the second access (R). In other words, at each time, the cache contains every previously used item whose next use is less than τ = R accesses in the future. Since there is only one memory access per time step, it follows U that the number of items in cache will never exceed τ. Since this policy minimizes C, it holds that for whatever value of M results, F is minimized. M can be tuned by changing the value of τ.

Denning’s working set policy (WS) is similar. The working set W (t, τ ), at memory access t, is the set of pages touched in the last τ memory accesses. At each access, the cache contains every item whose last use is less than τ accesses in the past. As in the VMIN policy, the cache size can never exceed τ. WS uses past information in the same way that VMIN uses future information. As with VMIN, the average memory usage varies when τ does.

Adaptations to Heterogeneous Memory Architectures

Compared with DRAM, phase change memory (PCM) can provides higher capacity, persistence, and significantly lower read and storage energy (all at the cost of higher read latency and lower write endurance). In order to take advantage of both technologies, several heterogeneous memory architectures, which incorporate both DRAM and PCM, have been proposed. One such proposal places the memories side-by-side in the memory hierarchy, and assigns each page to one of the memories. I propose that the VMIN algorithm described above can be modified to minimize total access latency for a given pair of average (DRAM, PCM) memory usage.

Using the following variables:

- n: Length of program’s memory access trace

- F: Miss/fault ratio (fraction of accesses that are misses to both DRAM and PCM)

- HDRAM: Fraction of accesses that are hits to DRAM

- HPCM: Fraction of accesses that are hits to PCM

- RF: Cost of a miss/fault (miss latency)

- RH,DRAM: Cost of a hit to DRAM

- RH,PCM: Cost of a hit to PCM

- MDRAM: Average amount of space used in DRAM

- MPCM: Average amount of space used in PCM

- UDRAM: Cost (“rent”) to keep one item in DRAM for one unit of time

- UPCM: Cost (“rent”) to keep one item in PCM for one unit of time

- rtfwd(b): The forward reuse time of the currently accessed item, b

Define the cost of running a program as C = nFRF + nHDRAMRH,DRAM + nHPCMRH,PCM + nMDRAMUDRAM + nMPCMUPCM, where we are now counting the cost of a hit to each DRAM and PCM, since the hit latencies differ. If at each access we have the choice to store the datum in DRAM, PCM, or neither, until the next access to the same datum, the cost of each access b is rtfwd(b) * UDRAM + RH,DRAM if kept in DRAM until its next access, rtfwd(b) * UPCM + RH,PCM if kept in PCM until its next access, and RF if it is not kept in memory. At each access, the memory controller should make the decision with the minimal cost.

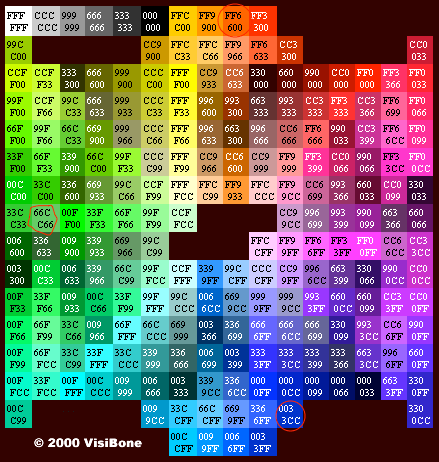

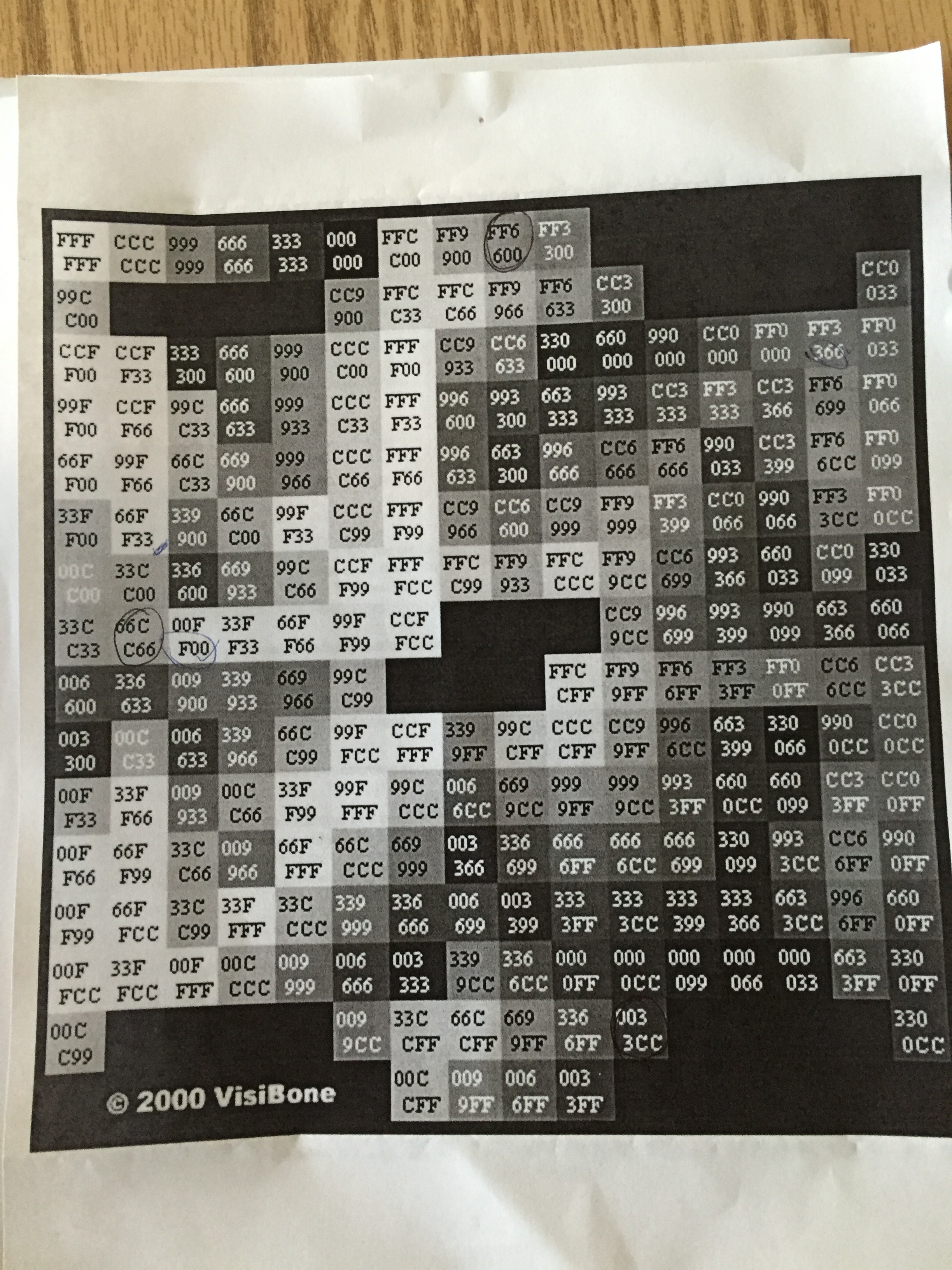

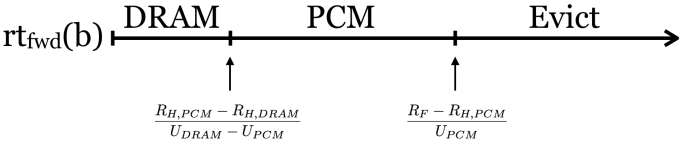

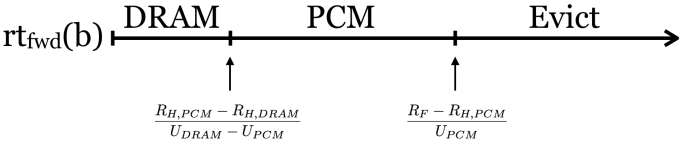

Of course, by minimizing the cost associated with every access, we minimize the total cost of running the program. The hit and miss costs are determined by the architecture, while the hit and miss ratios, and the DRAM and PCM memory usages are determined by the rents (UDRAM and UPCM, respectively). The only tunable parameters then are the rents, which determine the memory usage for each DRAM and PCM. The following figure (which assumes that UDRAM is sufficiently larger than UPCM) illustrates the decision, based on rtfwd(b):

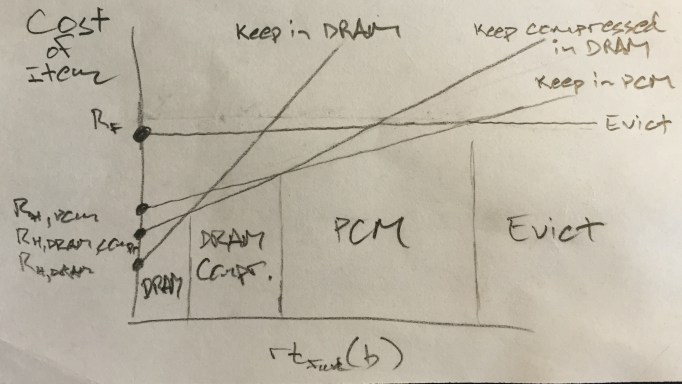

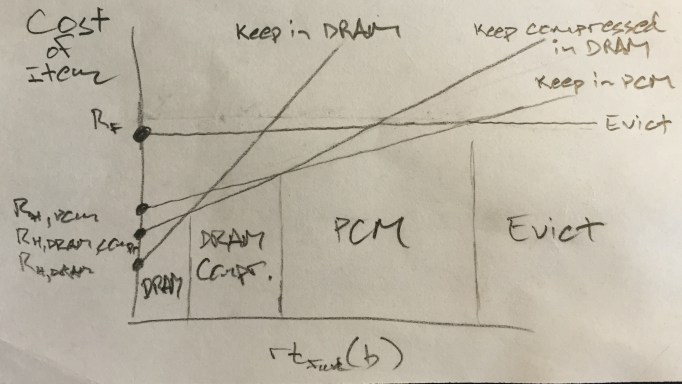

Update: an alternative diagram, showing the cost of keeping an item in each type of memory vs. the forward reuse distance (now including compressed DRAM):

Since the only free parameters are UDRAM and UPCM, this is equivalent to having two separate values of τ, τDRAM and τPCM in the original VMIN policy. The WS policy can be adapted by simply choosing a WS parameter for each DRAM and PCM.

If DRAM compression is an option, we can quantify the cost of storing an item in compressed form as rtfwd(b) * UDRAM \ [compression_ratio] + RH,DRAM_compressed.