This week, billions of people, 1.4 in mainland China, are enjoying their longest holiday of the year. It is a tradition time to reflect, mark an entry in this juncture in time, and share with others. With that spirit, here are my thoughts on the fifth day of the Year of Horse.

A recurring theme in traditional Chinese drama is the contrast between those who help others in urgent need and those who only add to the wealth of the rich. This sentiment appears in the book Slapping the Table in Astonishment (Part One), published around 1627—roughly 200 years after Zheng He’s ocean voyages. The original text reads:

“世间人周急者少,继富者多。为此,达者便说:’只有锦上添花,那得雪中送炭?’ 只这两句话,道尽世人情态。”

This translates to: “In this world, few help those in desperate need, while many add to the fortunes of the already wealthy. Thus, the wise observe: ‘There are always those who gild the lily, but who brings charcoal in the snow?’ These words capture the true nature of human relationships.”

The idea of helping others—going out on a snowy night to deliver firewood to those without heat—once defined my understanding of charity. Before coming to Rochester, I believed that was exactly what charity meant: helping others. Living in Rochester, however, my perspective has changed.

Rochester has a rich legacy. In 1960s and 70s, the “Nifty Fifty” stocks are a group of high-growth, large-cap stocks popular with institutional investors and widely regarded as “one-decision”, that is, buy and never sell. Three of these are in Rochester: Kodak, Xerox, and Bausch & Lomb. George Eastman, who founded Kodak, had a wealth of $100 million (2 billion today) and gave most of it away: $50 million to University of Rochester including Eastman music school and $20 million to MIT (anonymously as Mr. Smith). In his late years, he suffered from a health condition which was extremely painful. After touring the new River Campus of University of Rochester, accompanied by then university president Rush Rhees, he returned home and committed suicide, leaving a brief note: “To my friends: my work is done. Why wait? G.E.”

Rochester is cited as the birthplace of the modern United Way movement. “Checking a box” on a payroll deduction form to donate and support the community is a direct descendant of this tradition. If just visiting, one would not see a difference, but living here for decades, I know how unusual for a city to have a deeply ingrained culture of giving back. Since around 2010, a few years after our second child was born, my family has been donating the equivalent of one dollar per person per day to United Way. In 2025, approximately 50,000 people donated about $16.7 million to this organization alone. The funds are used to support programs run by local charitable organizations. Many people, including us, also donate directly to these groups. I know people who volunteer in these programs. For example, one of our children’s music teacher and her husband volunteer one day each week doing cleaning work at Ronald McDonald House. The picturesque house sits by the canal and a short distance from the UR Hospital, with 24 private bedrooms to house terminally ill children, at no cost to their families. I feel fortunate to be able to donate to United Way and support volunteers who help others. But this is still not the whole meaning of charity.

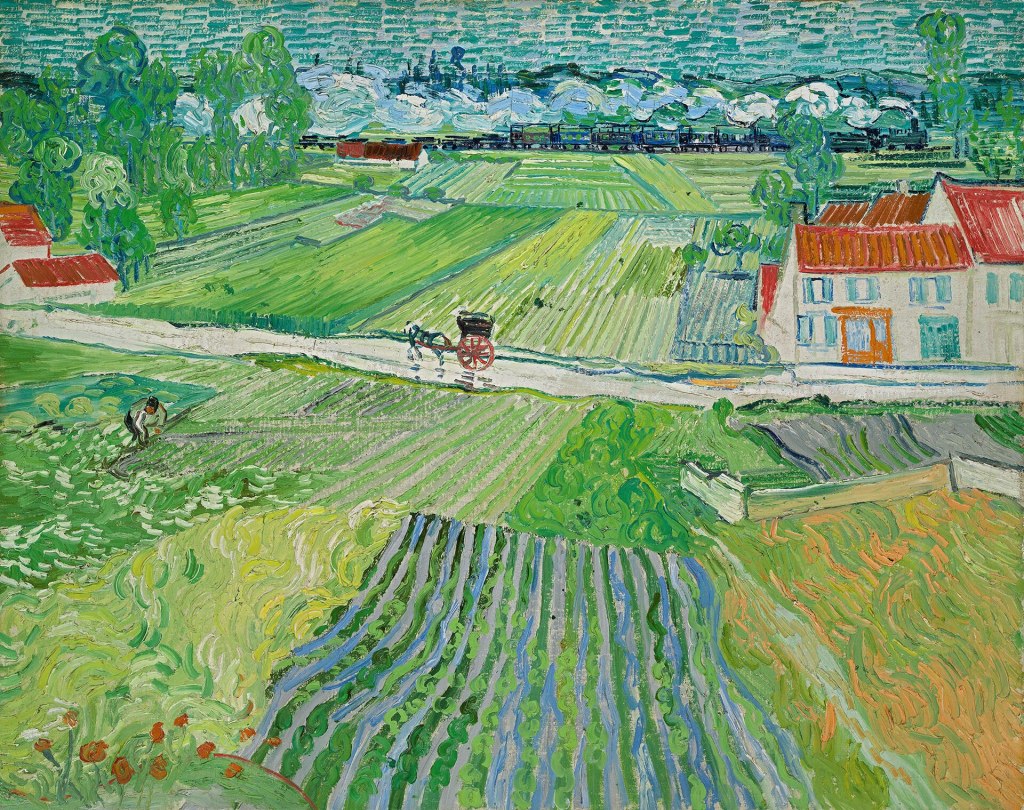

Today I saw a passage by Vincent van Gogh, who wrote in 1882 to his brother Theo Van Gogh (who supported him through his life and died only 6 months after Vincent died).

What am I in the eyes of most people — a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person — somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then — even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart. That is my ambition, based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion. Though I am often in the depths of misery, there is still calmness, pure harmony and music inside me. I see paintings or drawings in the poorest cottages, in the dirtiest corners. And my mind is driven towards these things with an irresistible momentum. I’m seeking. I’m driving. I’m in it with all my heart. What would life be if we had no courage to attempt anything. (based on translation used by @soulxsigh on TikTok)

Here is what charity truly means: It is not only about helping others—it is also about allowing ourselves to be inspired. Whether it is someone enduring a cold winter night without heat, someone donating their time to lift others up, or someone uncompromisingly charting their own life path, we draw inspiration from them. And we will not be the only ones who find new strength and meaning in their example. A life well lived is one filled with moments of inspiration. In this light, our charity is simply investing our wealth to live a better life—first and foremost for ourselves.

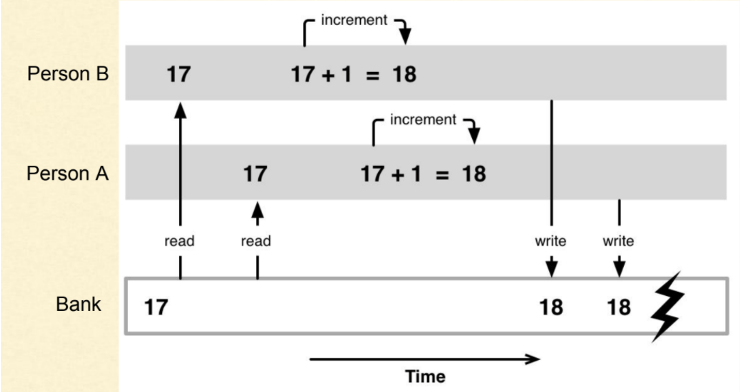

Below is van Gogh’s painting titled Landscape with a Carriage and a Train, with a horse in the center (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landscape_with_a_Carriage_and_a_Train). Wishing everyone a happy time in the Year of the Horse. 马到成功 (Mǎ dào chéng gōng) — may you succeed in arriving.

Fun fact: In 2020, Rochester United Way received a record $35 million donations. The unusual total is due to the historic $20 million gift from MacKenzie Scott.